- 1. 1. Core Characteristics: Why Humic Acid and Potassium Humate Behave Differently

- 1.1. Potassium Humate: The Soluble, Fast-Acting Activated Derivative

- 1.2. Side-by-Side Characteristic Comparison

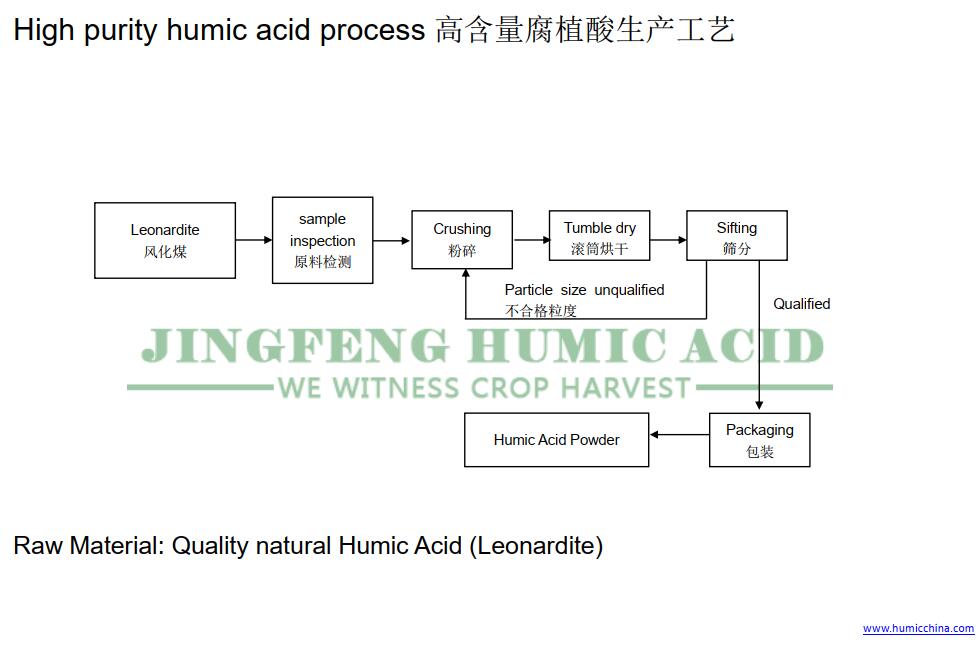

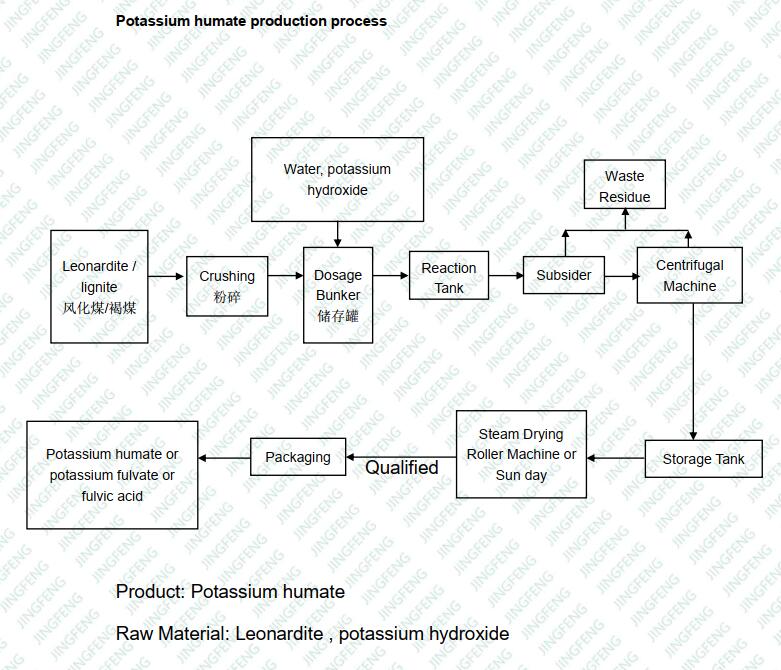

- 2. 2. Production Process: How Raw Humic Acid Becomes Potassium Humate

- 3. 3. How to Choose Between Humic Acid and Potassium Humate

- 4. Final Takeaway: Complementary, Not Competitive

While humates and humic acid are often discussed together, understanding the distinction between raw humic acid and its activated derivative—potassium humate—is critical for choosing the right product for your agricultural or environmental needs. These two substances share a common origin in organic matter, but their chemical properties, production processes, and real-world applications differ significantly. Below, we break down their core differences in characteristics and production methods, along with how these differences impact their performance in soil and crop care.

While humates and humic acid are often discussed together, understanding the distinction between raw humic acid and its activated derivative—potassium humate—is critical for choosing the right product for your agricultural or environmental needs. These two substances share a common origin in organic matter, but their chemical properties, production processes, and real-world applications differ significantly. Below, we break down their core differences in characteristics and production methods, along with how these differences impact their performance in soil and crop care.

1. Core Characteristics: Why Humic Acid and Potassium Humate Behave Differently

Humic acid, often referred to as “humic acid raw powder” in agricultural markets, is the unprocessed or minimally processed fraction derived from organic-rich sources like leonardite (the most common source) or lignite. Its characteristics are tightly linked to its natural, unmodified state:

- Origin and Composition: At its core, humic acid is essentially concentrated, screened leonardite or lignite. Leonardite itself forms from ancient, partially decomposed plant and animal matter (humification), where the primary component is humus—and humus is largely made up of humic acid. This means raw humic acid retains the chemical structure of its source material, with high carbon content but minimal alteration.

- Solubility: A Defining Limitation: The biggest constraint of raw humic acid is its poor water solubility. It does not dissolve in neutral or acidic water (the pH range of most agricultural soils, which typically falls between 5.5–7.0). It will only dissolve in strongly alkaline solutions (pH > 8.0), such as those mixed with lime or sodium hydroxide. This insolubility means it cannot be easily applied via irrigation systems (drip, sprinkler, or foliar sprays) and struggles to mix uniformly with water.

- Reactivity and Bioavailability: Due to its low solubility, raw humic acid breaks down very slowly in soil. Beneficial soil microbes must first decompose the large, complex molecules before their nutrients (carbon, micronutrients) become available to plants. This leads to slow-acting effects: improvements in soil structure or nutrient retention may take weeks or even months to become visible.

- Key Traits for Use: Its insolubility isn’t a complete drawback, however. Raw humic acid excels at long-term soil building: it binds to soil particles to improve aggregation (reducing compaction) and acts as a “reservoir” for nutrients, even if those nutrients aren’t immediately accessible. It’s ideal for applications where gradual, sustained soil health improvement is the goal—such as pre-planting soil amendments for perennial crops or lawns.

Potassium Humate: The Soluble, Fast-Acting Activated Derivative

- Origin and Composition: Potassium humate is created by reacting raw humic acid (from leonardite or lignite) with a strong alkaline substance—most commonly potassium hydroxide (KOH), though sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or ammonia water are sometimes used for other humate salts (e.g., sodium humate, ammonium humate). This reaction “neutralizes” the acidic functional groups in humic acid and replaces them with potassium ions, transforming the molecule into a water-soluble salt.

- Solubility: The Game-Changing Advantage: Unlike raw humic acid, potassium humate is highly water-soluble across a wide pH range (typically 5.0–9.0)—the exact range of most agricultural soils and irrigation water. This solubility means it can be easily mixed with water and applied via any irrigation method: drip systems, sprinklers, foliar sprays, or even as a seed soak. It distributes uniformly in soil and can be directly absorbed by plant roots or leaves.

- Reactivity and Bioavailability: The activation process breaks down large humic acid molecules into smaller, more reactive fragments, boosting both activity and chelation capacity. Chelation is the ability to bind to micronutrients (iron, zinc, manganese) and make them more soluble for plants—potassium humate’s chelating power is 2–3x stronger than raw humic acid. This translates to fast-acting results: farmers and gardeners often see improvements within 1 week, including:

- Enhanced soil water retention (critical for drought-prone areas).

- Longer, more branched crop roots (improving nutrient and water uptake).

- Reduced nutrient deficiencies (e.g., less iron chlorosis in tomatoes or corn).

- Key Traits for Use: Potassium humate is designed for immediate plant support. It’s perfect for seasonal crops (e.g., vegetables, fruits) where rapid growth or stress recovery is needed—such as after transplanting, during fruit development, or in response to drought or salinity. Its solubility also makes it a top choice for hydroponic or soilless growing systems, where water-soluble nutrients are a must.

Side-by-Side Characteristic Comparison

To clarify the differences, here’s a quick breakdown of their key traits:

| Trait | Humic Acid (Raw Powder) | Potassium Humate (Activated) |

| Solubility | Insoluble in neutral/acidic water; soluble only in strong alkali | Highly soluble in water (pH 5.0–9.0) |

| Bioavailability | Low (slow decomposition by soil microbes) | High (direct absorption by roots/leaves) |

| Reaction Speed | Slow (effects visible in 4–8 weeks) | Fast (effects visible in 1–2 weeks) |

| Chelation Capacity | Moderate (limited to soil-bound nutrients) | High (binds and delivers micronutrients to plants) |

| Ideal Application | Long-term soil building (pre-plant amendments) | Immediate crop support (irrigation, foliar sprays) |

2. Production Process: How Raw Humic Acid Becomes Potassium Humate

Raw humic acid don’t have any chemical additives. No reaction, so it’s also treated as high purity leonardite or lignite.

Potassium humate is reacted by leonardite and potassium hydroxide. The humic acid in potassium humate is totally activated. Could be absorbed by plants easily.

3. How to Choose Between Humic Acid and Potassium Humate

- Choose Humic Acid If: You want to build long-term soil health (e.g., improving clay or sandy soil structure), reduce compaction over time, or add a slow-release carbon source for soil microbes. It’s best applied as a pre-plant soil amendment (mixed into the top 6–8 inches of soil) or as a topdressing for lawns/perennials.

- Choose Potassium Humate If: You need fast-acting results (e.g., supporting seedling growth, recovering stressed crops, or boosting fruit quality), or if you plan to use irrigation systems (drip, sprinkler) or foliar sprays. It’s also ideal for hydroponics or soilless mixes, where water solubility is non-negotiable.